To get batters out in the big leagues, Randy Jones needed to make them hit the ball on the ground.

That’s what the Padres left-hander did when he pitched his most impressive game _ a 10-inning one-hitter to beat the Cardinals in 1975. Twenty-two of the 30 outs were ground balls.

When batters lifted the ball in the air against Jones, bad stuff often happened _ like the game at St. Louis when Hector Cruz and Lou Brock hit inside-the-park home runs to beat him in 1976.

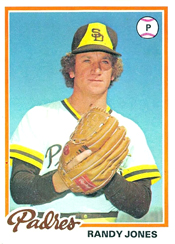

A 20-game winner the season after he lost 22, and recipient of the 1976 National League Cy Young Award, Jones was 75 when he died on Nov. 18, 2025.

Portrait of a prospect

Randy Jones grew up in Brea, Calif., near Anaheim. Another prominent big-league pitcher, Walter Johnson, spent his teen years there after his family moved from Kansas. Looking to cash in on an oil boom, the Johnsons settled in the village of Olinda, now a Brea neighborhood.

Jones liked baseball and followed the Dodgers (his favorite players were Sandy Koufax and Tommy Davis). He showed promise as a pitcher. In 1963, when Jones was 13, his school principal asked a friend, Washington Senators left-hander Claude Osteen, to give the teen a pitching lesson. Osteen emphasized to Jones the importance of throwing strikes and keeping the ball down in the zone.

“He had a good sinker, even at 13,” Osteen recalled to The Sporting News, “but he threw sidearm. I advised him to throw more overhanded, or three-quarters.”

Jones went on to pitch in high school and at Chapman College, but arm ailments caused him to lose velocity. In explaining why he’d offered Jones only a partial baseball scholarship in 1968, University of Southern California (USC) coach Rod Dedeaux told columnist Jim Murray, “He’s only got half a fastball.”

Padres scouts Marty Keough and Cliff Ditto saw enough to recommend Jones. The Padres picked him in the fifth round of the 1972 amateur draft. Keough (who later scouted for the Cardinals) told Dave Anderson of the New York Times, “He threw strikes … and he got people out.”

Welcome to The Show

Duke Snider and Jackie Brandt, the former Cardinal, were Jones’ managers in the minors, but the person who had the biggest influence on him there was pitching instructor Warren Hacker. A former Cub and the uncle of future Cardinals coach Rich Hacker, Warren Hacker “taught me to throw a better sinker,” Jones told the New York Times. “He showed me how to place my fingers differently and how to apply pressure with them.”

The sinker became the pitch that got Jones to the big leagues just a year after he was drafted. His debut with the Padres came in June 1973 versus the Mets. The first batter to get a hit against Jones was 42-year-old Willie Mays, who blasted his 656th career home run over the wall in left-center at Shea Stadium. Boxscore

A week later, Jones made his first start, at home versus the Braves, and Hank Aaron, 39, became the second player to slug a homer against him. It was the 692nd of Aaron’s career. “The home run came off a fastball outside,” Aaron told United Press International. “The kid got it up. Had it been down a little, I probably would have popped it up.” Boxscore

Facing Aaron and Mays, who were big-leaguers before Jones started kindergarten, wasn’t the end of the rookie’s storybook experiences. His first big-league win came in the ballpark, Dodger Stadium, where Jones’ father took him as a youth to cheer for the home team. Jones beat them, pitching a four-hitter and getting 18 outs on ground balls. Dazed, he told The Sporting News, “I finished the ninth inning and didn’t realize the game was over.” Boxscore

Reconstruction project

Based on Jones’ seven wins as a rookie, including a shutout of the 1973 Mets (who were on their way to becoming National League champions), the Padres had high hopes for him in 1974, but Jones instead posted an 8-22 record. Though the Padres scored two or fewer runs in 17 of those losses, lack of support wasn’t the sole reason for the poor mark. Jones’ pitching deteriorated as the season progressed (4.46 ERA in August; 6.23 in September.) “My confidence was completely shot,” he told The Sporting News.

After the season, the Padres hired pitching coach Tom Morgan. As Angels pitching coach, Morgan turned Nolan Ryan into an ace by getting him to alter his shoulder motion. “If you ask me who had more influence on me than anybody in my career, I’d have to say Tom Morgan,” Ryan told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram.

Morgan did for Jones what he’d done for Ryan. “He said I was opening up too soon with my right shoulder, that I wasn’t pushing off the rubber with my left foot, that I was pitching stiff-legged and that I was throwing all arm and no body,” Jones said to The Sporting News.

In short, Jones told the Los Angeles Times, Morgan “basically reconstructed my delivery … He gave me the fundamentals to be consistent.”

The turnaround was immediate. Jones was 20-12 with a league-best 2.24 ERA in 1975. He won two one-hitters _ versus the Cardinals and Reds.

Luis Melendez (who batted .248 for his career, but .571 against Jones) singled sharply to open the seventh for the lone St. Louis hit. The Cardinals managed just two fly balls. “It was the best game of my career because of all the ground balls the Cardinals hit,” Jones told the Associated Press. Boxscore

Two months later, facing a lineup featuring Pete Rose, Johnny Bench and Tony Perez, Jones gave up only a double to Bill Plummer and beat a Big Red Machine team headed for a World Series championship. He got 20 outs on ground balls. Boxscore

After Jones induced 22 ground-ball outs in a three-hit shutout of the Braves, pitcher Phil Niekro said to The Sporting News, “You get the feeling he can make the batter ground the ball to shortstop almost any time he wants to.” Boxscore

Location and movement

Jones basically relied on a sinker and slider. Roger Craig, who became Jones’ pitching coach (1976-77) and then manager (1978-79), said Jones threw a sinker 60 to 70 percent of the time, and a slider the other 30 to 40 percent. “Craig estimates that Jones’ sinker breaks down five to 10 inches and breaks away up to six inches from a right-handed batter,” the New York Times reported.

Jones’ fastball was clocked at about 75 mph. Foes and teammates alike kidded him that it was more like 27 mph.

In rating pitchers for the Philadelphia Daily News, Pete Rose said “the two who gave me the most trouble were Jim Brewer and Randy Jones.”

Rose was a career .183 hitter versus Jones. “Randy had him crazy,” Padres catcher Fred Kendall told the New York Times. Kendall recalled when Rose stood at the plate and yelled to Jones, “Throw hard, damn it, throw hard.”

Cardinals first baseman Ron Fairly told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in 1975, “He has a sinker. That’s all it is, and not a very hard one at that.”

Fairly’s teammate, Keith Hernandez, saw it differently. In his book “I’m Keith Hernandez,” the 1979 National League batting champion said of Jones, “Anyone who dismissed him as a soft tosser missed the point. With a hard sinker and a wicked hard slider, much like Tommy John’s, Randy threw his fastball hard enough to keep hitters off-balance.”

As Jones told The Sporting News, “My fastball is good enough that I can come inside on right-handed hitters and keep them honest.”

Jones also put batters out of synch by working fast. A game with Jones and Jim Kaat as starting pitchers was completed in one hour, 29 minutes. Jones finished a two-hitter versus Larry Dierker and the Astros in one hour, 37 minutes. Boxscore and Boxscore

Six of Jones’ 1975 wins came in games lasting less than one hour, 45 minutes.

Ups and downs

Jones followed his 20-win season of 1975 with a league-leading 22 wins and the Cy Young Award in 1976. He also was first in the league in innings pitched (315.1) and complete games (25), and had a stretch of 68 innings without issuing a walk.

Though the Cardinals were a mess (72-90) that season, they played like the Gashouse Gang when facing Jones. He was 1-3 against them.

On June 18, 1976, the Cardinals snapped Jones’ seven-game winning streak with a 7-4 victory at Busch Memorial Stadium.

In the fourth inning, with Ted Simmons on second, Hector Cruz (hitless against Jones in his career) drove a high pitch deep to left-center. Willie Davis leapt and got his glove on the ball, but, when he hit the wall, the ball popped free and shot toward the infield. Cruz circled the bases for an inside-the-park home run.

An inning later, with Don Kessinger on first, Lou Brock (a career .190 hitter versus Jones) punched a pitch to right-center. The ball hit a seam in the AstroTurf, bounced over Davis’ head and rolled to the wall. Brock streaked home with the second inside-the-park homer of the game. “The odds are real strong on that not happening again,” Jones told the Post-Dispatch. Boxscore

In October 1976, Jones had surgery to repair a severed nerve in the bicep tendon of his left arm. He never had another winning season, finishing with a career mark of 100-123.

Terrific tutor

Back home in Poway, Calif., Jones placed an ad in a local newspaper, offering private pitching instruction. Joe Zito signed up his son, 12-year-old Barry Zito, at a cost of $50 per lesson. “We had it,” Joe Zito recalled to the New York Times. “It was the food money.”

The lessons took place in the backyard of Jones’ hilltop home. Getting pitching tips from a Cy Young Award winner was something “I would kind of marvel at,” Barry Zito told the Associated Press.

According to the New York Times, Jones tutored Zito, a left-hander, once a week for more than three years and videotaped their sessions. Jones used a tough-love approach. One time, after Zito kept throwing pitches into the middle of the strike zone, Jones yelled, “We’re not playing darts. Never throw at the bull’s-eye.”

Zito recalled to the Associated Press, “When I did something incorrectly, he’d spit tobacco juice on my shoes, Nike high-tops we could barely afford.”

Reminded of that, Jones told the wire service, “I had to get his attention, and that worked with Barry. He didn’t focus really well when we first started. By the time, he got into his teens, he locked in. He just kept getting better.”

In 2002, two years after reaching the majors with Oakland, Zito was a 23-game winner and recipient of the American League Cy Young Award.