On the irony of baseball’s evolving relationship with gambling and how exile, in some ways, magnified the legends of Pete Rose and Shoeless Joe Jackson.

There was change made to Major League Baseball this week that has got me thinking about things like the cruelty of life, the legacy of consequence, and the fragility of man.

You know, as one does.

Manfred announced Tuesday that he was changing the league’s policy on permanent ineligibility, saying bans would expire at death. It was something I had thought seemed fair for a long time — a lifetime ban, not a permanent one — but there is a sort of level of macabre that comes with that thinking. A sort of posthumous absolution, not granted in life, only in death.

And maybe that’s the nature of consequence. It lingers. It defines. It outlives the person it is imposed upon.

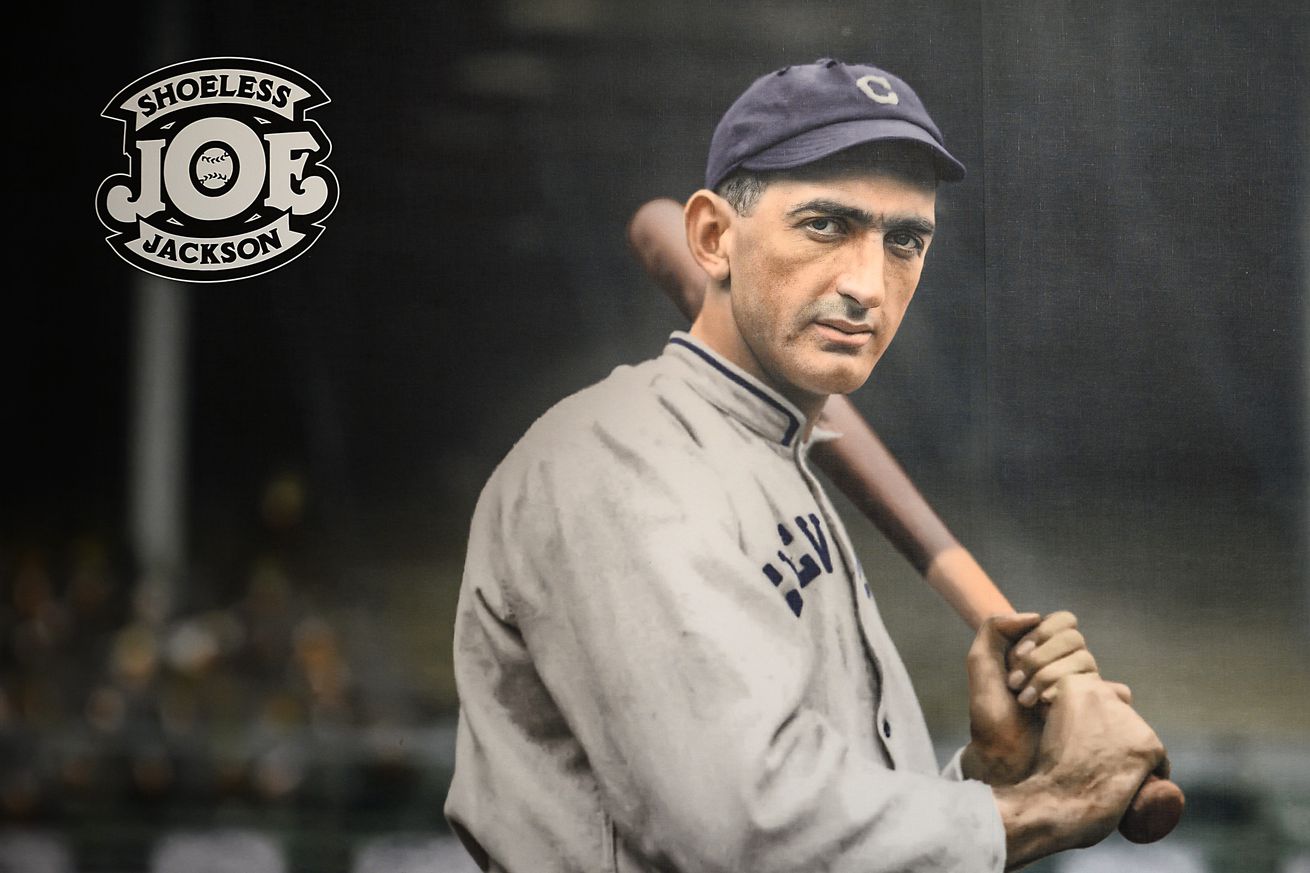

I very distinctly remember when I learned about Shoeless Joe Jackson as a kid. There was a book on the shelves at school called Shoeless Joe and Me by Dan Gutman. To be honest… I never actually read it, but I stopped at it every time on my way to the Nancy Drew books. The cover was a giant portrait of Joe’s face; his name printed in bold letters: Shoeless Joe. It always caught my attention. The story, according to the back of the book, followed a boy who learned about Jackson’s banishment from baseball due to the Black Sox scandal, and, with a level of sympathy maybe only possible in childhood, traveled back in time to try and stop him from being cast out.

It resonated with me, even without reading the book. The idea of someone being so great at something—so completely meant for it—and yet somehow unable to do it brought about a level of profound sadness. It felt unfair in a way that only a child can fully feel unfairness—before cynicism, before understanding the complexities of punishment and reputation. I wanted to go back in time myself, to undo it, to fix it, because the alternative seemed unbearable.

And this was an unfairness felt even before I learned the true scope of it. The level of inequity in the game at that time.

Because Shoeless Joe Jackson wasn’t the first, nor would he be the last, to be shut out of baseball despite greatness. The game has a long history of exclusion, whether for scandal, for circumstance, or simply for the unwritten rules of the era.

The color barrier kept generations of gifted Black players from the Major Leagues before Jackie Robinson broke through in 1947. Players with undeniable talent spent their careers in the Negro Leagues, their names forgotten or their records unrecognized for decades. And even once the game integrated, reputations and alliances determined who was protected and who was cast out.

Shoeless Joe and Pete Rose — who passed away September 30 and was also reinstated nearly thirty years after he first applied for reinstatement in September of 1997 — were punished in the name of baseball’s integrity. And yet, many of the game’s most revered figures weren’t spotless. Hall of Fame pitcher Gaylord Perry was notorious for scuffing and doctoring baseballs, manipulating his pitches well beyond legal limits. It was an open secret, something he joked about throughout his career, yet he was celebrated as a master of deception rather than ostracized for breaking the rules.

Then there was the steroids era—where players like Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens remain outside the Hall of Fame due to scandal, even as baseball profited from their accomplishments in real time. The home run chase, the record-breaking seasons, the excitement that filled stadiums and sold tickets—it was a spectacle baseball eagerly embraced. The league likely knew what was happening, but as long as the numbers soared, it had every reason to turn a blind eye, at least at the time.

Then, even more than bending the rules, than questionable reputations, than outright scandals— there was Ty Cobb. A player so fiercely competitive, so ruthlessly aggressive, that his legacy remains tangled in myth, controversy, and raw talent. Cobb was baseball’s first great superstar, his name synonymous with excellence. Yet, for all his records—for all his brilliance with a bat—his reputation carried something darker. He was known for sharpening his spikes, sliding in violently to injure opponents, throwing fists as readily as baseballs, and maintaining a ferocity that defined him just as much as his skill.

And then there were the whispers. The rumors of game-fixing, of questionable dealings. Accusations never quite proven, but never fully dismissed. And yet, Cobb was inducted into the Hall of Fame without hesitation. No banishment. No exile. No lifetime of waiting for redemption that would only come in death.

The message, whether intentional or not, was clear: Certain players could bend the rules and remain icons. Players skirted the edge of legality, but some were celebrated for their craft while others were condemned for their sins. Others—like Shoeless Joe and Pete Rose—became examples, reminders of baseball’s supposed moral authority. Because punishment in baseball has never been entirely about guilt, not really. It has been about image. About who is allowed to be redeemed, and who must remain an example.

Which is why the contradictions of today’s game feel especially glaring. Of course, there’s a difference between simply placing bets and betting on a sport you are directly involved in—there’s a clear risk to integrity when a player or manager wagers on their own games. But even acknowledging that distinction, baseball’s evolving stance on gambling makes its past punishments feel hollow.

The same institution that barred Pete Rose for life because of his bets now profits from partnerships with sportsbooks. Sponsorships, odds integrated into broadcasts, live betting woven into the fan experience—gambling isn’t just tolerated, it’s actively encouraged. What was once baseball’s greatest sin is now a pillar of its business model. The game has long chosen who to exile and who to enshrine. And now, as it embraces gambling for profit, the punishments of the past feel less like steadfast moral stands and more like convenient, selectively enforced judgments.

So what, exactly, does exclusion mean? What does redemption require? If Shoeless Joe and Pete Rose are now eligible for the Hall of Fame, it cannot be because baseball has suddenly decided their legacies matter. It’s because time has made their exile irrelevant, right? They no longer threaten the image of the game. They are relics, ghosts of a bygone era, finally given permission to step inside—but only when they can no longer speak for themselves.

Maybe that’s the final cruelty. They spent their lives waiting for redemption, only to receive it when they weren’t here to see it.

But maybe, just maybe, their greatest revenge is that their legacy—defined by absence, by longing, by the myth of exile—was always greater than any Hall of Fame induction could ever be. Maybe legacy isn’t just about official recognition. It’s about the stories that refuse to disappear. And maybe, in the end, exile wasn’t their downfall—it was the thing that made them immortal.

But that’s just what I’ve been thinking about! Here a full list of people that had been permanently banned from baseball.

Happy Sunday!