Yogi Berra wasn’t kidding when he said, “It ain’t over till it’s over.”

Berra’s playing days certainly appeared to be over in October 1963 when he became manager of the Yankees. “I’ll have enough trouble managing,” he said to the Associated Press in explaining why he was done playing.

Berra’s playing days certainly appeared to be over in October 1963 when he became manager of the Yankees. “I’ll have enough trouble managing,” he said to the Associated Press in explaining why he was done playing.

More than a year later, though, the St. Louisan was behind the plate, catching for the 1965 Mets in a spring training game against the Cardinals.

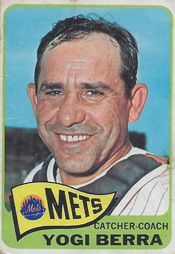

Five months earlier, as Yankees manager, Berra’s club lost to the Cardinals in the 1964 World Series. Afterward, Berra was fired and replaced by the Cardinals’ manager, Johnny Keane. The Mets hired Berra to be a player-coach on the staff of the manager he played for the most as a Yankee, Casey Stengel.

Never say never

Berra appeared in a World Series in 14 of 18 seasons as a Yankees player. A three-time recipient of the American League Most Valuable Player Award, he totaled 2,148 hits and 1,430 RBI with the Yankees.

After the 1963 World Series, Yankees manager Ralph Houk was moved to the front office and Berra replaced him, getting a one-year contract for $35,000, a $5,000 cut from his salary as a player. Asked to describe his feelings about the job, Berra told the New York Daily News, “I just hope I can stay in the same shoes as Houk did.” Asked what he’d learned from those who managed him, Berra said, “You can observe a lot just by watching.”

Though the 1964 Yankees won the American League pennant with the best record (99-63) in the majors and reached Game 7 of the World Series, Berra was fired. As the Daily News noted, “It is generally believed the Yankees brass felt Berra had lost disciplinary control of the ballplayers.”

The Yankees offered him a contract to remain as a consultant. Berra accepted, but got them to include an escape clause. A month later, in November 1964, he jumped to the Mets. In addition to coaching, Berra would be added to the playing roster as a catcher and pinch-hitter if he performed well enough at spring training.

Old-timers’ days

On the first day of spring training for the 1965 Mets at St. Petersburg, Fla., observers had flashbacks to another era. Berra took cuts in the batting cage. Pitcher-coach Warren Spahn, the former Braves ace, instructed prospects on the mound. Four-time 1936 Olympic gold medalist Jesse Owens, listed as Mets track coach, led players in conditioning exercises. Former Cardinals manager Eddie Stanky, director of player development, was in uniform, directing infield drills.

As Joseph Durso of the New York Times noted, “The Mets opened their spring training circus while manager Casey Stengel (approaching 75) stood like a ringmaster behind home plate bellowing, ‘Yes, sir, come see the amazing Mets.’ ”

Berra was the main attraction, drawing cheers from onlookers when he put on a catcher’s mitt to warm up a teenage pitcher and then again at batting practice.

A couple of weeks later, on March 14, Stengel selected Spahn (nearly 44) and Berra (nearly 40) to start in a Grapefruit League game against the Cardinals. Philadelphia Daily News columnist Larry Merchant described the pitcher-catcher combination as “the oldest, ugliest battery in captivity.”

When the Cardinals took batting practice, their vice president, Stan Musial, 44, came out in uniform and joined in. Musial, who retired from playing two years earlier, “slammed out a dozen drives,” Cy Kritzer of the Buffalo News reported.

Some of the Mets, including Berra and Spahn, gathered to watch him. After sending a pitch to the bleachers in right, Musial said to them, “You fellows inspire me. If you ancients can make a comeback, maybe I’ll try it, too. I’m only nine months older than you, Spahnie.”

Spahn replied, “Don’t do it, please. This league is rough enough without you to worry about.”

According to the Buffalo News, Stengel chimed in. “You’re a vice president, ain’t you?” he said to Musial. “You can do what you want to do. If you’re aiming for a comeback, we can use you. I’d have some fun in those late innings, sending you and Yogi to pinch-hit.”

Musial replied, “Yogi will hit. Hitting is like swimming. If you learn early enough, you’ll hit long after you’ve lost the rest of your skills.”

When the game began, the sight of Spahn on the mound and Berra behind the plate “was enthusiastically greeted by the Geritol set” that made up most of the crowd of 2,989 at Al Lang Field, the Daily News reported.

Spahn’s first pitch, a fastball that cut across the plate for a strike to Lou Brock, sent “a murmur of approval” through the stands, columnist Red Smith noted.

Brock then beat out a high bouncer over the mound for an infield single and Curt Flood walked on a 3-and-2 pitch. After getting two strikes on the next batter, Bill White, Spahn spun a roundhouse curve from a sidearm delivery, fooling White, who swung and missed for strike three, then stood there and laughed. “The pitch fooled me, too,” Berra told Red Smith. “I didn’t expect it to act like that.”

Spahn worked three innings and allowed three runs. Berra was hitless. He flied out against Bob Gibson and whiffed versus rookie Nelson Briles. “He struck me out with a heck of a quick-dipping sinker,” Berra told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “The kid has a real arm.”

Asked by the New York Times what was the hardest thing to do in catching a game for the first time since September 1963, Berra replied, “Bend down.”

Like old times

On April 27, two weeks after the Mets began the 1965 season, Berra was activated to the playing roster while maintaining his coaching duties. In his first week, he made one pinch-hit appearance. Then came one last moment of glory.

A couple of hours before the Mets played the Phillies on May 4 at Shea Stadium, Berra was talking with Newsday’s Joe Donnelly. “Give me a cigarette,” Berra said to the reporter. After inhaling deeply, Berra continued, “Maybe I’ll play tonight.” When Donnelly chuckled, Berra barked, “Why not? Let’s find out.”

Moments later, Berra met with Stengel and asked to catch. Stengel put him in the No. 6 spot in the batting order.

When Berra saw Phillies ace Jim Bunning before the game, he needled him: “I wish you were pitching. If I couldn’t get a hit off you, I’d know I was through.”

The Phillies’ starter instead was Ray Herbert, a pitcher Berra faced often during the 1950s when both were in the American League.

Berra’s first test came on defense in the first inning and he did well, making a tough putout at the plate. With Johnny Callison on third, Alex Johnson hit a chopper that was fielded by pitcher Al Jackson. As Callison charged home, Jackson threw to Berra, “who had the plate guarded beautifully,” Red Foley of the Daily News reported. “Callison stopped short, ducked, then tried to veer around Yogi,” but Berra ‘”was spry enough to pin him with the ball.”

Berra got a standing ovation when he batted with Ed Kranepool on second and Joe Christopher on first, two outs, in the first. Herbert threw a pitch around Berra’s eyes and he lined it to center for a single, his first National League hit.

It also should have been his first National League RBI, but this being the Mets, the hit didn’t deliver a run. Center fielder Cookie Rojas threw to third, where Christopher was tagged out before the slow-moving Kranepool reached the plate.

As the game unfolded, Al Jackson got into a good groove with Berra catching him. The Phillies couldn’t score.

With the Mets ahead, 1-0, in the seventh, reliever Gary Wagner gave up a leadoff single to Berra. “I was going to take him out for a pinch-runner,” Stengel told the Philadelphia Daily News. “I only wanted to catch him five innings.”

Jackson interceded, saying to Stengel, “Leave him in there.”

Berra took second on Ron Swoboda’s single, then scored on Roy McMillan’s single to center. When Swoboda reached second, he applauded while watching Berra cross the plate. “I get such a kick out of it because I think a lot of people decided he was no longer capable of this,” Swoboda told Newsday.

Berra’s run turned out to be the difference in a 2-1 Mets triumph. Jackson pitched a complete game and struck out 11. In the book “Baseball’s Greatest Players,” Jackson said, “Yogi was … a huge asset to me … You looked in for the sign like he had some magic. He did.” Boxscore

Stepping aside

When he tried to catch five days later against the Braves, it was a different story. Berra went hitless, striking out three times, and made an error, dropping a pop fly. “Essentially, his reflexes weren’t up to the major league standards,” the New York Times declared.

Berra knew that this time his playing days really were over, and he called it quits. “It’s hard for me to see the ball,” he confessed to the New York Daily News.

As he told Joe Donnelly, “I always felt when a guy couldn’t hit a fastball, he might as well hang up the bat.”

Berra remained with the Mets as coach until 1972, when he took over as manager after the death of Gil Hodges and led them to a pennant a year later.