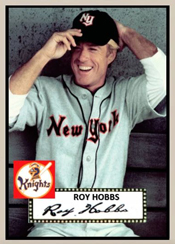

In Bernard Malamud’s novel, “The Natural,” the central character, Roy Hobbs, wears baseball uniform No. 45. In the movie version, though, his number is 9.

The decision to switch from No. 45 to No. 9 was made by Robert Redford, the actor who portrayed Hobbs in the 1984 film. Redford did it to honor his favorite ballplayer, Ted Williams, who wore No. 9 for the Red Sox.

The decision to switch from No. 45 to No. 9 was made by Robert Redford, the actor who portrayed Hobbs in the 1984 film. Redford did it to honor his favorite ballplayer, Ted Williams, who wore No. 9 for the Red Sox.

“When I was growing up, the only real hero I ever had was Ted Williams,” Redford told Esquire magazine in 1988.

An actor, director and producer, as well as an ardent environmentalist, Redford had leading roles in several quality movies, including “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” (1969), “The Candidate” (1972), “The Sting” (1973), “Three Days of the Condor” (1975) and “All the President’s Men” (1976). He won an Academy Award for best director in the first feature film he directed, “Ordinary People” (1980). Redford was 89 when he died on Sept. 16, 2025.

Books, art and baseball

Redford’s father, Charles, and mother, Martha, were married three months after he was born in Santa Monica, Calif. His father was a milkman and the family resided in an ethnically diverse neighborhood. “We weren’t impoverished, but we were on the lower end of things,” Redford recalled to Esquire in 2017.

As a youth, “Redford spent hours in the children’s section at the local library where he became fascinated with books on Greek and Roman mythology,” according to CNN.

(In explaining his vision for “The Legend of Bagger Vance,” the 2000 sports fantasy movie he directed, Redford told the Los Angeles Times, “The library is where I got this mythology.”)

Redford’s other boyhood interests included drawing (“In class, under the table, I would draw because I was bored,” he told Esquire) and baseball.

“I loved Ted Williams,” Redford told the Denver Post in 1986. “What I loved most was that he was good and had that arrogance because he knew he was good.”

Redford played youth baseball _ “I wanted to be a professional ballplayer,” he said to the Boston Globe in 2016 _ and, like Ted Williams, he batted left-handed.

Until he was 14, Redford spent summers in Austin, Texas, where his maternal grandfather had a place on a lake, according to the Austin American-Statesman. Meanwhile, Redford’s father, seeking a better income, became an accountant and moved the family to suburban Van Nuys in California’s San Fernando Valley. Redford found Van Nuys to be conformist and dull.

“When we moved to the Valley, I felt like I was being tossed into quicksand,” Redford recalled to the Los Angeles Times in 1997. “There was no culture. It was very oppressive. I would have preferred the Hispanic neighborhood I grew up in.”

(Redford told Joanne Stang of the New York Times in 1966, “I really loved Los Angeles when I was growing up _ the tar streets and all the space _ but, each time I’ve come back, there have been a few more developments and a few more supermarket complexes … Finally there was no resemblance to what I knew as a kid, so I don’t feel any connection to it now, and that’s sad.”)

At Van Nuys High School, Redford was a classmate of Don Drysdale, the future Hall of Fame pitcher. Van Nuys won San Fernando Valley League championships in each of Drysdale’s three varsity seasons. Later, when Redford became famous, some published reports incorrectly suggested he and Drysdale had been baseball teammates. Jim Heffer, a pitcher on those Van Nuys title teams, said Redford never played for the Van Nuys varsity. “I never once saw Redford so much as with a glove in his hand,” Heffer told the Los Angeles Times in 1993.

Young and restless

Another myth involving Redford and baseball relates to his days as a student at the University of Colorado. Contrary to many published reports, Redford didn’t go there on a baseball scholarship. “We have no evidence to suggest that he received a baseball scholarship or ever played on the baseball team here,” University of Colorado athletic department spokesman Steve Hurlbert told Mitchell Byars of Axios Boulder in September 2025.

In 1966, Redford said to the New York Times, “I really went to Colorado to ski and be in the mountains, which I love. I told everybody at home I intended to be a lawyer to get them off my neck. I took a liberal arts course, then just art, and my grades fell apart.”

Redford spent most of his college days (and nights) partying. “I wasn’t ready to be a student,” he told the Associated Press in 1987. “(Colorado) was definitely known as a party school. The temptations were great.”

In 1955, late in his freshman year, Redford’s mother died of a blood disorder associated with the birth of twin girls, who lived only a short while. According to the New York Times, “her death left him angry and disillusioned.”

“I felt betrayed by God,” Redford recalled to biographer Michael Feeney Callan.

In 2017, Redford told Michael Hainey of Esquire, “My mom felt I could do anything. She was the only one who told me that, the one who really did believe that I was going to do things. She encouraged me to constantly be opened up. I took it all for granted as a teenager. When she died … the regret that I had was that I couldn’t thank her.”

Redford quit college during his sophomore year in 1956. (Twenty-one years later, at a University of Colorado commencement, Redford was given an honorary degree, citing his establishment of a nonprofit educational enterprise, the Sundance Institute in Provo Canyon, Utah, devoted to the arts. His father, Charles, attended the ceremony. According to Scripps Howard News Service, Redford held the degree over his head, “smiling broadly, with both fists clenched in triumph,” and said it was “certainly every bit as important as the Oscar.”)

After dropping out of college, Redford worked in a California oil refinery until he earned enough money to head to Europe, where he hoped to become a painter.

“I was in Cannes and I was hitchhiking and I couldn’t afford a room,” Redford recalled to Esquire. “I was sleeping underneath a pier, in a sleeping bag, and in the daytime I’d walk the streets. I met this older woman. She must have been 20 years older than me. She ran a little shop. We became friends and then we got extremely close. So I lived there for a while.”

In Paris, according to the New York Times, Redford sold sidewalk sketches for pocket money. In Florence, he made $200 from a show of canvases and used the cash to make his way to New York. Redford briefly attended Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, intending to be a set designer. A friend recommended the American Academy of Dramatic Arts as a place to learn about the theater. Redford went there and took up acting.

Parts in television and on Broadway led to Redford being cast in film. A breakthrough was co-starring with Jane Fonda in “Barefoot in the Park” (1967). Redford’s good looks helped get him roles. According to the Los Angeles Times, though, he turned down the lead in 1967’s “The Graduate” because “nobody will believe I am a 21-year-old college student who never got laid.”

Hollywood treatment

Redford was 47 when filming for “The Natural” took place in 1983. War Memorial Stadium in Buffalo was the site of many of the film’s baseball scenes.

Gene Kirby, a baseball consultant for the movie, recalled to the New York Times, “Getting ready for a scene to be shot in the rain, Redford came onto the field, escorted by an assistant holding a large umbrella over his head. I was standing alongside the camera at second base. As he approached me, he looked over and said, ‘I’ll bet Ted Williams never came onto the ballfield this way.’ ”

Former Cardinals minor-leaguer Tony Ferrara, batting practice pitcher for the Mets and Yankees, had a bit part in the film. “I did all the pitching to Robert Redford, who was a good hitter,” Ferrara told Dave Anderson of the New York Times. “His idol was Ted Williams and he stood up there like Ted Williams, with the bat straight up. I knew where and how he liked the ball … He hit a few out on me.”

Redford had hoped Williams would join him on the set.

“When I was making ‘The Natural,’ I tried to get hold of him,” Redford said to Mike Barnicle of Esquire in 1988. “I wanted to make that movie with him. I wanted to make it in Fenway Park and wear Williams’ No. 9. I wanted to shoot the last scene there … the home run … the lights exploding … me wearing No. 9. God, I would have gotten out of the business after that. That would’ve been a career for me.”

Redford told the Boston Globe that when he invited Williams to watch the filming, Williams, in turn, invited him to go fly-fishing, but Redford said he “never had the pleasure” of following up on the offer. Redford and Williams never met.

(Describing himself as a lifelong Red Sox fan, Redford told the Globe in 2016, “I had the joy of my life a few years ago when I sat behind the catcher at Fenway and they beat the Yankees.”)

Bernard Malamud’s 1952 novel, “The Natural,” was inspired by a 1949 incident involving Phillies first baseman Eddie Waitkus, who was shot in the chest by a deranged admirer, 19-year-old Ruth Steinhagen, in a Chicago hotel room. New York Times reviewer Harry Sylvester hailed Malamud’s work as “a brilliant and unusual book.”

Unlike the novel, the 1984 movie, “The Natural,” was Hollywood hokum. As the Times noted, the movie had “a happy, even exalted, ending for its baseball hero instead of the author’s profoundly pessimistic and sardonic conclusion.”

Times movie critic Vincent Canby wrote that the filmmakers “transform something dark and open-ended … into something eccentricly sentimental.” Movie clip

American audiences, naturally, lapped up the sappiness. “The Natural” grossed $48 million in the United States and the film became part of baseball lore. Several props from the movie, including the complete Roy Hobbs uniform and his bats, “Wonder Boy” and “Savoy Special,” were donated to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y.