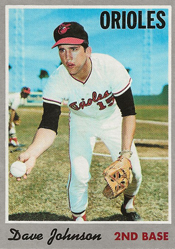

When Davey Johnson was a second baseman for the Orioles in the early 1970s, long before the time when analytics became as much a part of the game as balls, bats and gloves, he voluntarily developed computer programs to construct optimized lineups and brought the data to manager Earl Weaver.

“I found that if I hit second, instead of seventh, we’d score 50 or 60 more runs and that would translate into a few more wins,” Johnson told the Baltimore Sun. “I gave it to him (Weaver), and it went right into the garbage can.”

“I found that if I hit second, instead of seventh, we’d score 50 or 60 more runs and that would translate into a few more wins,” Johnson told the Baltimore Sun. “I gave it to him (Weaver), and it went right into the garbage can.”

Later, as a big-league manager, Johnson put his computer skills to good use, leading the Mets to a World Series title in 1986 and taking four other clubs (1988 Mets, 1995 Reds, 1996 Orioles and 1997 Orioles) to league playoff finals.

Johnson, however, wasn’t a push-button manager. He relied on instincts as well as calculations. “You’ve still got to allow for your gut feeling,” he told the New York Times.

“You gamble against the odds sometimes,” Johnson said. “If not, you’ll become a statistic in somebody else’s computer.”

A three-time American League Gold Glove Award winner, Johnson played in four World Series, including in 1966 when he became the last batter to get a hit against Sandy Koufax. According to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, when reminded of that years later, Koufax quipped, “Yeah, that’s why I retired.” Boxscore

With the Braves in 1973, Johnson slugged 43 home runs, breaking the big-league record for a second baseman held by Rogers Hornsby, who hit 42 for the 1922 Cardinals. (Marcus Semien topped Johnson with 45 for the 2021 Blue Jays.) Johnson also played in the same lineup with two home run kings _ Hank Aaron of the Braves and Sadaharu Oh of the Yomiuri Giants.

As a player and as a manager, Johnson was a persistent foe of the Cardinals. He had a career .456 on-base percentage against them, and batted .424 with 11 RBI in 10 games versus St. Louis in 1973. When Johnson managed the Mets, he and Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog dominated the National League East Division in the mid-1980s. From 1985-88, Johnson’s Mets and Herzog’s Cardinals each won two division titles. Johnson was 82 when he died on Sept. 5, 2025.

Facts and figures

Davey Johnson was born while his father, Lt. Col. Frederick A. Johnson, was in the U.S. Army during World War II. Lt. Col. Johnson was serving in an advanced tank corps on the front line in North Africa when he was captured. He spent the rest of the war in prison camps. The officer tried three times to escape. Malnourished, Lt. Col. Johnson weighed 83 pounds when liberated, according to a newspaper report. He retired from the military in 1962, the year his son Davey signed with the Orioles after playing shortstop for Texas A&M and studying veterinary medicine.

While with the Orioles, Johnson earned a degree in mathematics from Trinity University in San Antonio and took graduate courses in computer science at Johns Hopkins University. “When he was a player … he was always asking why,” Orioles executive Frank Cashen told the New York Times. “I think the main influence on him was his mathematics.”

Earl Weaver said to the Baltimore Sun, “Davey was always the type of player that was inquisitive. He always wanted to know what I was trying to do and why I was trying it. That is the type of player who is going to be a successful manager.”

Naturally, his Orioles teammates nicknamed him Dum-Dum. “He was a guy who was always thinking about things,” pitcher Jim Palmer told the Sun. “Very cerebral, maybe even to the point of overanalyzing a situation.”

(According to the Sun, Palmer once said, “Johnson thinks he knows everything about everything.” Told of Palmer’s comment, Johnson laughed and said, “No, actually, I know a little about everything.”)

Frank Cashen recalled to the New York Times, “He was a different sort of cat. In salary negotiations, he was in a class by himself. He’d come in with a stack of computer printouts to prove he should bat someplace else in the lineup, or that he deserved more money. He had all these statistics.”

Or, as Cashen put it to the Sun, “Davey was always single-minded, willing to swim against the tide.”

During Johnson’s playing days with the Orioles (1965-72), personal computers were uncommon. So Johnson got permission to use the computer system at National Brewing, a company run by Orioles owner Jerry Hoffberger.

“When you apply statistics to something like baseball, you’ve got the problem of the number of limited chances,” Johnson said to the New York Times. “If you flipped a coin 10 times, you might get nine heads, but if you flipped it 1,000 times, you’d come close to 500 heads. The Standard Deviation Chart says a 5 percent deviation in 1,000 times is acceptable. One day, Jim Palmer was pitching and he was wild. So I trotted over and told him, ‘Jim, you’re in an unfavorable chance deviation situation. You might as well quit trying to hit the corners and just throw it over the plate.’ He told me to get back to second base and shut up.”

Big bopper

With first-round draft choice Bobby Grich ready to take over at second base, the Orioles traded Johnson to the Braves in November 1972. The Braves got him to replace Felix Millan, who was dealt to the Mets. They hoped Johnson would provide good glovework. They weren’t expecting him to hit with power. Johnson’s highest home run total with the Orioles was 18 in 1971.

However, with the 1973 Braves, Johnson turned into … Hank Aaron. Johnson clouted 43 homers and drove in 99 runs. With 151 hits and 81 walks, he produced an on-base percentage of .370 and had fewer than 100 strikeouts.

The top four home run hitters in the National League in 1973 were the Pirates’ Willie Stargell (44), Johnson (43) and his Braves teammates Darrell Evans (41) and Hank Aaron (40).

The Braves’ ballpark was a home run haven dubbed “The Launching Pad.” Johnson popped 26 homers at home in 1973 and 17 on the road. Aaron told Jesse Outlar of the Atlanta Constitution, “He doesn’t go for any bad pitches. He makes them pitch to him, waits for his pitch. He has a great swing.”

According to Thomas Boswell of the Washington Post, Johnson would “crowd the plate, dare the pitchers to bean him (and) feast on the inside pitch.”

Whether in Atlanta or St. Louis, Johnson was tough on Cardinals pitchers. On June 9, 1973 at Atlanta, he had three hits, including a home run, and a walk, scored three runs and knocked in two. Two months later in a game at St. Louis, Johnson again produced three hits, including a homer, and a walk. He drove in four runs, scored once and stole a base. Boxscore and Boxscore

In April 1975, Johnson and the Braves parted ways. He spent two unhappy seasons playing in Japan, where he clashed with popular manager Shigeo Nasashima and was booed. Returning to the U.S., Johnson finished his playing career with the Phillies (1977-78) and Cubs (1978).

Candid and formidable

After three seasons in the Mets’ system, two as a manager; one as an instructor, Johnson returned to the majors as Mets manager in 1984 and made them contenders. Frank Cashen, who had moved from the Orioles to the Mets, told the New York Times, “Davey makes moves in a game that are so good they are absolutely eerie. Other managers are thinking of the moves they’ll make this inning. Davey is thinking of the moves he’ll make three innings from now.”

As a sign of the respect he had for Johnson, Jim Leyland, a future Hall of Fame manager, called him “McGraw,” in reference to the manager with the most National League wins, John McGraw. Whitey Herzog said to the Post-Dispatch of Johnson, “I always thought he did a pretty good job of running the ballgame.”

Johnson’s managing methods usually worked, but his personality sometimes got him crossways with the front office. As Joseph Durso of the New York Times noted, Johnson “speaks so bluntly that people duck or cringe.”

It’s part of the reason he didn’t stay in one place for too long. He managed the Mets (1984-90), Reds (1993-95), Orioles (1996-97), Dodgers (1999-2000) and Nationals (2011-13).

“Davey Johnson isn’t the easiest guy to get along with,” Tony Kornheiser of the Washington Post wrote. “You wouldn’t want him living next door. He is abrasive and confrontational … Davey tends to manage from the position that he’s smarter than you and everybody else in the room. His history is that he wears out his welcome rather quickly.”

However, Kornheiser concluded, “There may be some discomfort about what Davey is as a manager, but here’s what Davey does as a manager: He wins.”

Mets pitcher Ron Darling, who majored in French and Southeast Asian history at Yale, told the New York Times, “I think of Davey the way I used to think of my father _ always pushing me to do better … He doesn’t walk through the locker room and chat with players about how they’re doing. That’s not his style … Davey expects you to do your job, period … I think there’s calculation in his being aloof. By not telling you what he’s going to do, he gains a little edge on you. If you carry it out far enough, though, it’s a sadistic edge.”

In 2012, 26 years after he managed the Mets to a World Series title, Johnson, nearly 70, still was successful. He led the Nationals to 98 wins, most in the majors. Their reward for that was a playoff matchup against the Cardinals, a team that finished fifth in the National League. In the decisive Game 5, the Cardinals rallied for four runs in the ninth on a pair of two-out, two-run singles from Daniel Descalso and Pete Kozma. Boxscore

Typically direct, Johnson said to the Associated Press, “Not fun to watch … We just need to let this be a lesson … learn from it, have more resolve, come back and carry it a lot farther.”