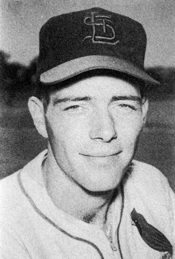

In September 1950, Bobby Tiefenauer was young, successful and in love.

A 20-year-old reliever for a Cardinals farm club in Winston-Salem, N.C., Tiefenauer threw a knuckleball that had batters swinging at air. His manager, George Kissell, credited him with making his team the best in the league.

A 20-year-old reliever for a Cardinals farm club in Winston-Salem, N.C., Tiefenauer threw a knuckleball that had batters swinging at air. His manager, George Kissell, credited him with making his team the best in the league.

Tiefenauer’s No. 1 fan was his sweetheart back home in the mining district of Missouri. Rosemarie Henson agreed to marry the pitcher at home plate before a game at Winston-Salem. The wedding date was set for Sept. 5, 1950.

On the morning of the big day, the ballclub’s business manager, Bill Bergesch, accompanied the couple to the county clerk’s office to obtain a marriage license. That’s when Bergesch learned the bride was 17. “We almost missed having this wedding,” Bergesch later told the Winston-Salem Sentinel.

Because Rosemarie was younger than 18, she needed the written consent of her parents in order for a license to be issued, the county clerk said. Rosemarie’s mother, who was in town for the wedding, promptly gave her consent, but dad was back in Missouri, working in a mine, the Sentinel reported.

The clerk said if the father could send a telegram of consent by 5 p.m. that day, the wedding could be held that night as scheduled at Southside Park. Frantic calls were made to Missouri. As the clock ticked, Bergesch paced the floor. “One might have thought he was the groom,” Carlton Byrd of the Sentinel observed.

A few minutes before 5, the father’s telegram arrived and the license was issued. “It was close, but we made it,” Bergesch told the Sentinel.

The couple rushed to the ballpark for the 7:30 p.m. ceremony. A total of 3,050 spectators came out. Tiefenauer had wanted the wedding held at home plate so that all his teammates could be present, the Winston-Salem Journal reported. He also made a request to George Kissell: The groom wanted to pitch in the game that night against the Burlington (N.C.) Bees.

The bride was dressed in a satin gown. Her matron of honor was Kissell’s wife. Tiefenauer wore a suit. The Rev. Mark Q. Tuttle, a Methodist pastor, officiated. After the service, “the couple moved under an archway of bats held by members of the Winston-Salem and Burlington teams,” the Journal reported.

The game began at 8:15. In the sixth inning, Kissell honored Tiefenauer’s request, sending him in to pitch. Tiefenauer’s mind may have been on other things. He faced five batters, plunking one with a pitch, walking another and giving up three hits, before being lifted.

Though his pitching that night was a dud, Tiefenauer’s marriage was a winner. It lasted for 50 years until his death in 2000.

No quit

Tiefenauer was from Desloge, 65 miles south of St. Louis and in an area of Missouri where mining of lead and zinc had been prominent. His high school didn’t have a baseball team, so Tiefenauer played sandlot ball and softball. A prep basketball talent, he got offers to play in college, but dreamed of pro baseball.

In the summer of 1947, after graduating from high school, Tiefenauer, 17, attended a Cardinals tryout camp in St. Louis and was signed to a pro contract. The club told him to report to minor-league spring training at Albany, Ga., in 1948. When he got there, however, he failed to impress and was sent home.

While playing softball, Tiefenauer found he could make his overhand throws around the infield move like a knuckler. He tried it with a baseball, too, with encouraging results. That summer of 1948, Tiefenauer, 18, went to a Cardinals tryout camp at Fredericktown, Mo., and told scout Joe Monahan he’d developed a knuckleball pitch. Monahan liked what he saw and signed him.

The Cardinals sent the teen to a Class D farm club in Tallassee, an Alabama cotton mill town on the Tallapoosa River in the Emerald Mountains. Tiefenauer returned there for a full season in 1949 and won 17. That earned him the promotion to Winston-Salem for 1950.

Dipsy-doo

The Winston-Salem club managed by George Kissell featured pitcher Vinegar Bend Mizell and second baseman Earl Weaver. Even at 19, Weaver was feuding with umpires the way he would years later as Orioles manager. In describing a Weaver plate appearance to the Winston-Salem Sentinel, Kissell said in 1950, “He really stands up there and talks to those umpires. He had a strike called on him on a bad pitch and he really squawked.”

Kissell chose Tiefenauer to be his top reliever, in part, because the knuckleballer could work multiple games in a row. It was a wise decision. Tiefenauer consistently secured wins for the team by baffling batters with the knuckler.

Fayetteville (N.C.) manager Mule Haas, the former outfielder who played in three World Series for the Philadelphia Athletics, said to the Sentinel, “I’ve seen a lot of guys who throw that dipsy-doo stuff, but this kid (Tiefenauer) has the stuff to become the best (knuckleballer) I’ve seen.”

Carolina League umpire Johnny Allen, a former big-league pitcher, told Kissell he’d never seen anyone throw a more effective knuckleball than Tiefenauer.

Kissell said to the Winston-Salem Journal, “If his first pitch is a strike, the batter had better look out, because he’s not going to see anything but those knucklers. I saw him make one pitch that dropped two feet just as it started across the plate.”

The bravest members of the Winston-Salem team were the catchers tasked with corralling Tiefenauer’s knuckleball. Bullpen catcher Preston Shepherd didn’t wear any protective face covering when he took Tiefenauer’s warmup throws because the team’s only catcher’s mask was worn by the starter.

“Preston Shepherd is now insisting we buy him a mask to wear in the bullpen,” Kissell said to the Journal. “The other night he got hit in the eye by one of Tiefenauer’s knucklers. He swears the ball hopped right over his mitt.”

Even with a mask, one of Winston-Salem’s regular catchers, Willie Osteen, told the Sentinel, “I sure hate to call for his knuckleball with runners on base. I’m afraid I can’t catch the ball.”

Winston-Salem won the league championship with a 106-47 record. Tiefenauer won 16, but Kissell said the reliever contributed to 50 of the team’s wins. “Bobby was certainly the key to the pennant,” Kissell told the Journal.

Reidsville (N.C.) manager Herb Brett said to the newspaper, “Tiefenauer is the difference between a championship team and a second-division club … A lot of those victories chalked up to other pitchers (were) saved by his relief pitching.”

More work, the better

Tiefenauer went on to have many more excellent seasons in the minors, including for 1953 Rochester (9-3, 2.31 ERA), 1958 Toronto (17-5, 1.89), 1960 Rochester (11-4, 3.14) and 1967 Portland (6-1, 1.87).

The major leagues were a different story. Tiefenauer’s record was 9-25 (including 1-4 for the Cardinals), with 23 saves. Usually, he didn’t get to pitch a lot and his control suffered.

For example, his three stints with the Cardinals:

_ 1952: Eight innings, 12 hits allowed, seven walks.

_ 1955: 32.2 innings, 31 hits, 10 walks.

_ 1961: 4.1 innings, nine hits, four walks.

“I just need a lot of work,” Tiefenauer told the St. Louis Globe-Democrat in March 1955. “When I do pitch often, I can get the knuckler over.”

Tiefenauer’s most productive time in the majors came in a stretch with the Milwaukee Braves. Brought up from the minors in mid-August, he had a 1.21 ERA in 29.2 innings for Milwaukee in 1963. Tiefenauer spent all of 1964 with the Braves, pitched 73 innings and led them in saves (13).

The next year, though, another knuckleball pitcher, rookie Phil Niekro, arrived in the Braves’ bullpen and Tiefenauer was shipped to the Yankees (whose manager, Johnny Keane, had him in the Cardinals’ system).

At the plate, Tiefenauer had trouble making solid contact regardless of what pitch was thrown. In 39 at-bats in the majors, he had one hit _ a double versus the Giants’ Jack Sanford, a 24-game winner that year. Boxscore

Overcoming adversity

Tiefenauer didn’t discourage easily. He persevered through setbacks more dire than roster demotions or transfers.

In early May 1957, Tiefenauer arranged for his wife Rosemarie and their three sons to leave their house in Desloge and join him for the summer in Toronto while he pitched for the minor-league Maple Leafs there.

A couple of weeks later, a tornado “cut a path of havoc six blocks wide” through Desloge, the Associated Press reported. The twister lifted Tiefenauer’s two-story white frame house off its foundation and moved it 200 feet into the middle of the street, the Globe-Democrat reported. One side of the house was blown out.

Tiefenauer said the tornado also took the roof off his parents’ house and his mother was knocked unconscious when struck by falling boards, the Associated Press reported. O.M. McLeod, a miner who watched the tornado hit Desloge, told the wire service it sounded like “a steam engine with burned out bearings pulling a string of freight cars.”

Two years later, Tiefenauer was at 1959 spring training with the Cleveland Indians when he injured his right arm practicing pickoff throws. He went home to Desloge and sat out the entire season.

At one point that summer, Cleveland general manager Frank Lane asked Cardinals trainer Bob Bauman to examine Tiefenauer’s arm. Bauman discovered the pitcher had circulatory trouble. “My arm started to come around after he worked on it,” Tiefenauer told The Sporting News.

Tiefenauer resumed pitching in 1960 and continued to play in the pros until 1969, the year he turned 40. After that, Tiefenauer worked for many years as a pitching coach in the Phillies’ system. He also was the bullpen coach for the 1979 Phillies on manager Danny Ozark’s staff.